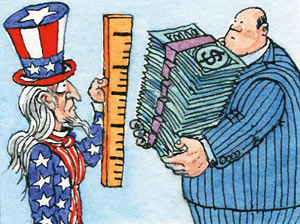

So far, Congress is taking a surprisingly sensible approach to the problem of pay

THE boardrooms of America were ready for misery. What else could result from Congress’s fury at runaway executive pay, outrageous Wall Street bonuses and handsome rewards for failure? The bosses can breathe a little more easily. The Corporate and Financial Institution Compensation Fairness Bill that won a healthy majority in the House of Representatives on July 31st turned out to be remarkably restrained—in some ways even too restrained (see article). However, with the Senate still to look at the legislation and the practical details of its implementation to be hammered out, there is plenty of time for that to change, for better or worse.

Despite the usual complaints about government heavy-handedness from Republicans and business lobbyists, the House bill contains none of the expected attempts to impose detailed limits on the size or structure of pay that would merit such alarm. Instead, as Barney Frank, the chairman of the House financial-services committee, puts it, “The question of compensation amounts will now be in the hands of shareholders and the question of systemic risk will be in the hands of the government.” This division of labour is right in principle. The difficult bit will be making it work in practice.

The shareholder part of the bill is fairly straightforward: shareholders will have the right to vote each year on the compensation packages and any golden parachutes of senior executives. Critics say this may allow what ought to be business decisions to become politicised, as activist shareholders—notably union pension funds—make mischief. But the experience in Britain, where shareholders have had exactly the same “say on pay” that the House voted for, suggests the opposite danger: that shareholders will rarely vote against a pay package and that when they do their vote, being merely advisory, will be ignored by management, as the board of Royal Dutch Shell did in May. Perhaps the vote, on both sides of the Atlantic, should be made binding. Even that would make little difference unless ways can be found to persuade institutional shareholders to vote for pay packages that serve their long-term interests.

The problem with financial pay

The other prong of the new legislation has the greater potential to go wrong. As defined, it is hard to quibble with. It gives financial regulators the right to obtain information about the incentive structure of pay in financial institutions, and to opine on whether that structure poses a risk to the stability of the financial system. Fair enough. After all, banks are different from other sorts of companies. And it seems pretty clear that badly designed pay arrangements contributed to the financial crisis: bankers, brokers and traders were rewarded handsomely for doing risky deals without being financially exposed if the deals went wrong.

But there are dangers. Systemic risk is due to be considered separately after the summer recess. Pay rightly should be part of that discussion: banks with risky pay structures need more capital than thriftier ones. But the systemic regulator will surely come under pressure to rule on specific individuals’ salaries for political reasons (ie, because the public thinks a bonus is outrageously big, not because it is endangering the system). As the “special master” appointed by Barack Obama to rule on pay in firms receiving government bail-out money is discovering, this is a hopeless task. The inconvenient truth is that banking will pay its best performers the sort of sums that outrage the public. The House bill makes it clear that it does not want the systemic-risk regulator to rule on the amounts of pay, only the way incentives are structured. Good. Now it is time to see if the Senate will be as wise.